In the following article, unless otherwise stated, when I use the term squat I am referring to the full or ‘deep’ squat where the crease of the hip drops below the level of the top of the knee.

Squats are one of the greatest exercises known to man. They help build massive strength in the legs and core and have helped athletes to run faster, jump higher and hit harder for decades. I’m not disputing that. This article is not meant to malign the squat in any way but it is a simple fact that they, like all exercises, are not perfect and there may be a way to improve upon them in certain situations. If you want to know how, read on.

The Problem with Squats (for athletic development).

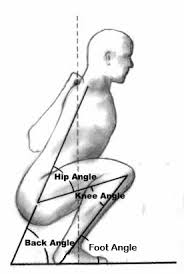

Most of the exercises we use to increase strength, power and overall athleticism have a point in their range of motion at which the lift is hardest (where the leverage is worst) and a point where it is easiest (where the leverage is best). The squat is no different. The bottom point of your squat is generally the hardest part of the lift. As you come up out of the ‘hole’ (and the leverages improve) the lift gets progressively easier. This is demonstrated by the fact that we can all quarter squat significantly more weight than we can squat below parallel. This creates two issues when it comes to their use in development of speed and power for athletes.

Issue One: Deep Squats for Strength Building

To demonstrate the first problem let’s use a rugby player as an example. Say we want to incorporate the back squat into our players program to build up his lower body strength with a view to increasing his sprinting speed.

We need to challenge his muscles with weights heavy enough to illicit strength adaptations so we test his one rep max (1RM) in the squat. This will establish his current strength level and give us a number to calculate training loads with.

We discover that he has a 1RM of 180 kilos, so we know that for the strength portion of his program we will program weights from 80-100% of 180kg, as this is the ‘sweet spot’ for maximising strength gains.

Leverages and the 1 Rep Max

Unfortunately, due to the mechanics of leverages, when we tested the players 1RM in the squat we were actually determining the most weight he could lift out of the ‘hole’ (the hole is the lowest point of a deep squat) for a single rep. He will have the strength in his legs to lift much more than this in a shallower ‘partial’ squat. This has implications for the percentages we are using to increase his leg strength.

Let’s say that our rugby player currently has the strength to lift 220 kilos in the quarter squat (where the leverages are more favourable). When we decided to program a set of 5 reps at 85% of his 1RM in a full squat, we were only achieving this percentage of his 1RM out of the hole .

In the upper (quarter squat) position of the lift using this weight we would only be operating at an intensity of around 70% of his max and this will reduce the closer to lockout he got. As a result we are no longer programming at an optimal intensity to induce maximal strength gains in this position.

The ‘Sports Specific Zone’

Unfortunately this ‘quarter squat’ position also happens to represent the most ‘sports specific’ point of the movement, where his joint angles most closely resemble those he will be working at on the field. This is true for most athletic activity. When a person jumps, sprints or changes direction they rarely get into a position where their hips descend lower than the quarter squat position.

Deep squat Quarter Squat Vertical jump Sprint

So having established that there is problem with the efficacy of the squat for optimally building strength in the ‘sports specific’ zone for athletes, what should we do with this knowledge?

No More Deep Squats?

The obvious answer is to do away with the full squat entirely. We have demonstrated that few athletes spend any appreciable time in a position which resembles the bottom portion of a squat so why not replace it with the quarter squat and get ‘specific’ with our training?! Well unfortunately it’s not that simple. You see, while quarter or ‘partial’ squats may have the edge over their full range of motion cousins in terms of force and power production, when equivalently heavy loads are used (as confirmed in a 2012 study comparing the two) there are other benefits to squatting deep which should not be dismissed.

1) The full squat leads to far greater glute and (possibly) greater hamstring recruitment than the quarter squat. Over-developing the quads at the expense of the posterior chain (glutes, hamstrings and lower back) can lead to muscular imbalance and increases the chance of injuries such as hamstring tears. Glute strength is also a major contributor to sprint speed and jumping ability.

2) Full squats have been shown to increase lower back stability and work the erector spinae in tandem with the glutes, further helping to ‘bullet proof’ your body.

Enter Bands and Chains

So if we want to reap the benefits of both the full and partial squat, maybe the answer is to find a place for them both in our training program. While that is one possible solution, it is certainly not ideal. The solution? Adding chains or bands!

Band and chain resistance has been used by Powerlifters since the 80’s. The concept is really pretty simple: bands are (usually) set up so that they are forced to stretch as you perform the concentric (upwards) part of a movement; chains so that they unravel from the floor, as demonstrated in this video.

Both provide a similar effect, which is to increase the resistance you are working against as your leverages improve. As bands stretch they get tighter, thus providing additional resistance for you to work against, and chains literally add to the weight of the bar as each link leaves the floor. Simply put, as you get in to a stronger position moving the bar gets harder not easier. Accordingly you get the benefits of both the full and partial squat!

Issue Two: Deep Squats for Power Building

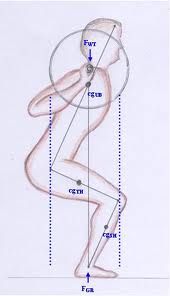

One of the primary reasons for including squats into the training programs of athletes is to develop explosive power in the legs. Power is defined as the speed (or strictly speaking the velocity) at which you can apply force. It is no good having incredible levels of leg strength if you are so slow at summoning it that you don’t have the chance to apply it to the ground when sprinting. One of the methods traditionally used to convert strength into power is through ‘speed squats’. Speed squats use lighter loads with a view to moving them extremely quickly (power = force x velocity!)

Slowing Down not Speeding Up

One of the drawbacks with squats (as well as nearly every other barbell movement besides the Olympic lifts) is that as we reach the end of the movement (the ‘sports specific’ zone), we are forced to decelerate precisely at the point at which we want to be at our most explosive (applying the greatest force as quickly as possible)! In their book Designing Resistance Training Programs, Fleck and Kraemer state that:

“When lifting a weight, the bar decelerates for a considerable proportion (24%) of the concentric [upwards] movement (Elliott, Wilson, and Kerr 1989). The deceleration phase increases to 52% when performing the lift with a lighter resistance (e.g., 81% of 1 RM) (Elliott, Wilson, and Kerr 1989).”

That’s right, instead of speeding up and achieving maximum power output as we finish the lift, we are actually slowing down!

Leverages (again!) and Hitting the Breaks

This occurs for two reasons, the first brings us back to the issue of leverages.

Firstly, at the bottom of a squat, where you will remember our leverages are at their worst, we are forced to powerfully accelerate the bar upwards to drive up out of the hole. To achieve this we produce a tremendous burst of power. However, as the leverages improve and the lift gets easier, our muscles no longer need to apply maximum force as the lift can be completed without it.

Secondly we must, by necessity, bring the bar to a complete stop at the end of the lift, and before any object comes to a halt it must first slow down! Furthermore the faster we get the bar moving, the longer we must spend slowing it down to stop it. This is at odds with the use of squats for the development of explosive power and has particularly severe implications for ‘speed squats’ performed with lighter weights. Imagine two identical cars approaching a red light, one is travelling at 20mph and the other 100mph. The faster car must hit the brakes long before the slower one to make sure it stops for the light! So instead of teaching our muscles to accelerate explosively, our speed squats may inadvertently be coaching us to slow down!

Chains and Bands to the Rescue!

By adding chains or bands to the bar we can reduce or eliminate both of these effects. By increasing the difficulty of the lift as our leverages improve (making it harder as we come up instead of easier) we force our muscles to continue to apply force for longer. In other words they can’t ‘cruise’ to lockout as they can with straight weight, but have to drive forcefully throughout the lift, reducing or eliminating deceleration.

In addition the added resistance near the top of the lift will actively act to decelerate the bar reducing the need for our own protective mechanisms to do it for us.

The combined effect is a longer, more forceful contraction. With speed squats we can use this mechanism to move the weight extremely quickly throughout the lift, increasing our rate of force development and creating fast, powerful muscles [see Why Strength Athletes Need Speed for an in depth look at ‘speed work’].

The Death of the Traditional Squat?

Am I suggesting that you away with traditional loading methods? No. Particularly if you are training for Powerlifting where rather than a means to an ends (increased running, jumping or hitting speed) the squat is an ends in itself. In other words it doesn’t matter whether or not you could strengthen the upper portion of the lift to a greater extent using chains or bands as the only thing you should care about is completing the lift and, in competition, the limiting factor will almost always be strength in the bottom part of the lift.

As for other athletes, don’t forget that while the ‘sports specific’ portion of the lift may not be targeted with the same percentage intensity with a traditional squat as the earlier part of the lift, the muscles will still be working to move a heavy load and so will get stronger as a result. Adding chains and bands can dramatically increase the intensity of a lift, which can be great but can also be extremely taxing, so their inclusion should be thought about carefully.

The one area in which I believe they should (almost) always be used is in conjunction with the ‘speed’ variations of lifts, where the goal is to increase power for sprinting, jumping and hitting. We don’t want to encourage the lifter to slow down and now we don’t have to!